Anecdotal evidence and empirical data show that Americans are infatuated with true crime, from cold-case television shows to mystery books. An unresolved mystery can be like catnip for the imagination, leaving the consumer transfixed and hungry for more.

The cases around which so much of the true-crime genre are based can remain open for years, even decades. But almost certainly none stretches back as far as the early years of the United States. This may be the greatest unsolved mystery of them all: What actually killed George Washington, the United States’ first president and a Revolutionary War hero?

The saga of Washington’s death actually began on Dec. 12, 1799, two days before his final breath. Washington was supervising work in the snow at his Mount Vernon, Virginia, estate; the snow turned to rain, and after returning home, Washington, ever punctual, went straight to dinner while still wearing his damp clothes.

The next day, Washington complained of a sore throat. His symptoms progressively worsened; he was coughing, his nose was running, his voice was becoming hoarse and he developed a fever. Washington was having difficulty swallowing and talking as well, and his breathing became so labored that, in the early morning hours of Dec. 14, he “awoke clutching his chest with a profound shortness of breath,” as PBS put it.

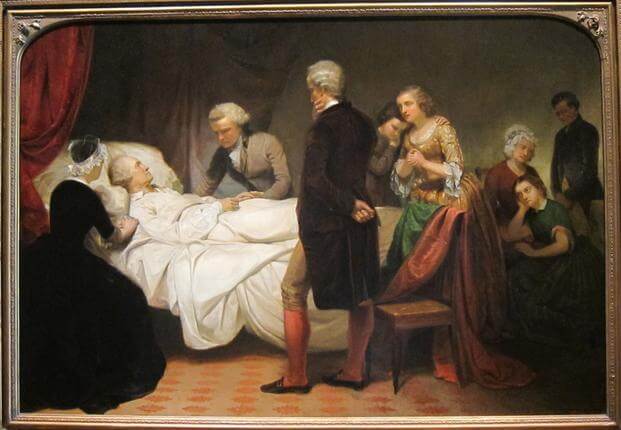

Three doctors were urgently summoned to Mount Vernon, including James Craik, who served under Washington during the American Revolution and was his longtime personal physician. Over the next 12 hours, at Washington’s request and against the pleading of his wife Martha, some of the president’s blood was removed during a process known as bloodletting, “to reduce the massive inflammation of his windpipe and constrict the blood vessels in the region,” per PBS.

In all, Washington was bled four times, losing more than 80 ounces of his blood -- or roughly 40% of his body’s supply. It didn’t work, causing the doctors to become increasingly desperate in their attempts to stymie Washington’s symptoms. They gave Washington a mix of molasses, butter and vinegar, which almost suffocated him; produced blisters on his throat to try to balance his bodily fluids; induced vomiting; gave him an enema; and had him gargle with sage tea and vinegar.

As the hours passed, though, Washington became resigned to his fate, telling Craik: “Doctor, I die hard, but I am not afraid to go. I believed from my first attack that I should not survive it. My breath cannot last long.”

Washington thanked his doctors. He did not make it through the night.

In the immediate aftermath of Washington’s death, his doctors considered four causes. The consensus was that Washington died of cynanche trachealis, also called the croup. That explanation has been highly debated, with various other theories -- a throat infection, quinsy, Ludwig Angina, Vincent’s Angina, diphtheria, strep throat and acute pneumonia -- put forth in the centuries since.

Some questioned the doctors’ decisions. Why did they remove so much of Washington’s blood, and did that contribute to his death? And why wasn’t a tracheotomy performed to help him breathe? The level of bloodletting performed on the 6-foot-3 Washington, however, likely would not have killed him, and the success rate of tracheotomies back then was spotty. “From the 16th century to the 19th century, a tracheotomy was generally regarded by surgeons as dangerous with a low chance of success, and as a result, few surgeons were willing to perform the procedure,” according to the News Medical website.

“Washington was old and sick by then,” Washington biographer James Thomas Flexner told The New York Times in 1999. “It was perfectly clear that he knew he was dying, and he was getting ready to die. The doctors did what they did in those days. To believe otherwise is moonshine.”

The most plausible explanation to emerge was that Washington died of acute epiglottitis -- a swelling of the lid of the windpipe that restricts airflow. Acute epiglottitis was first advanced as a cause of Washington’s death in the late 1830s, and it has been espoused more recently by both Dr. David Morens, a senior adviser at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Maryland, and Peter Henriques, author of “He Died as He Lived: The Death of George Washington.”

While acute epiglottitis is uncommon today, Washington exhibited classic symptoms of the disorder. “It’s really quite a frightening disease,” Henriques told The Washington Post in 1999. “The epiglottis may swell to more than 10 times its normal size, gradually shutting off the patient’s ability to either breathe or swallow.”

As the circumstances surrounding Washington’s death recede further into the past, though, we likely never will know definitively what killed him. From accounts of his death, we can at least know that Washington did not fear dying, as these were his final words:

“I am just going! Have me decently buried, and do not let my body be put into the vault less than three days after I am dead. Do you understand me? … Tis well!”

Washington was buried at Mount Vernon on Dec. 18, 1799. He was 67 years old.

-- Stephen Ruiz can be reached at stephen.ruiz@military.com.

Want to Know More About the Military?

Be sure to get the latest news about the U.S. military, as well as critical info about how to join and all the benefits of service. Subscribe to Military.com and receive customized updates delivered straight to your inbox.